How I got robbed of my first kernel contribution

Context

Around a year and a half ago, I’ve asked my former company for some time to work on an issue that was impacting the debugging capabilities in our project: gdbserver couldn’t debug multithreaded applications running on a PowerPC32 architecture. The connection to the gdbserver was broken and it couldn’t control the debug session anymore. Multiple people have already investigated this problem and I had a good starting point, but we still weren’t sure in which software component the issue lied: it could have been the toolchain, the gdbserver, the Linux kernel or the custom patches we applied on top of the kernel tree. We were quite far away from finding the root cause.

Investigating the issue

After diving into the existing analysis for this issue and channeling my

google-fu, I’ve had my first breakthrough: an email

thread

which not only described the same symptoms as our issue, but also pointed to

the exact

commit

which introduced it. The patch that introduced the bug moved the definition of

thread_struct thread from the middle of the task_struct to the end, a

seeminlgy innocuous change.

After debugging the issue, this is what Holger Brunck observed

What I see is that gdbserver sends for each thread a SIGSTOP to the kernel and waits for a response. The kernel does receive all the signals but only respond to some of them in the error case. Which then matches with my “ps” output as I see that some threads are not in the state pthread_stop and then the gdbserver gets suspended.

The low-level issue was that after interacting with gdbserver, some threads were in the wrong process state and gdbserver couldn’t control them anymore.

I’ve spent 3-4 days reading commit descriptions related to the PowerPC

architecture and the changes around task_struct, trying to figure out whether

this issue was solved in subsequent kernel versions (spoiler: it was not).

I’ve moved thread_struct thread around to determine when the issue reproduced

and used pahole to inspect

task_struct’s layout. I’ve used

ftrace to figure out

when the threads of the debugged process were scheduled and that’s how I

realized this could be a memory corruption issue: the threads that were stuck

were only scheduled once, unlike the other ones. I’ve originally dismissed that

this could be a memory corruption issue because in the original

thread

it was mentioned that:

the content of the buffer is always zero and does not change. So at least no one is writing non-zero to the buffer.

That’s what I get for not verifying that the structure isn’t overwritten with zero bytes (always validate your assumptions).

I remembered that the x86 architecture has debug registers that could be used to trigger data write breakpoints. In fact, this is how I solved a bug back in my earlier days as a software engineer. Sure enough, PowerPC also implements a similar capability with the help of the DABR register.

I’ve investigated how I could use hardware breakpoints on Linux and I ended up implementing a linux kernel module based on this excellent stackoverflow answer. This allowed me to place a hardware breakpoint on the __state field to figure out who on earth writes to it.

Finding the bug

And that’s how I found the issue: my custom kernel module showed the stack

traces from the places where the __state field of task_struct was being

written to. I’ve noticed an outlier which revealed a buffer overflow in

ptrace_put_fpr (used by the POKEUSER API). This led to important fields from

task_struct getting overwritten, such as __state, which stores the state of

the process and it’s also used by the kernel to keep track of which processes

are stopped by the debugger.

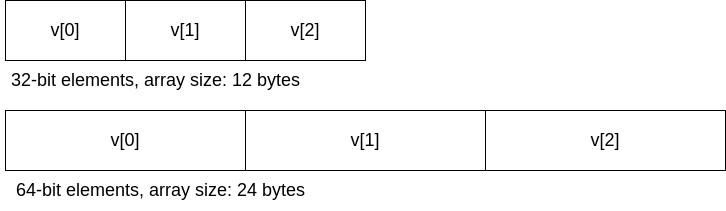

The cause of this overflow? Taking an index meant to be used with an array of

32-bit elements and indexing an array of 64-bit elements. There were 64 indexes

that addressed the FPR, so the total addressable memory was 64 * 8 = 512

bytes. But there were only 32 entries in the fp_state.fpr array, which means

that the available memory was only 32 * 8 = 256 bytes. That allowed the user

(aka gdbserver) to write up to 256 bytes past the end of the array.

Sending the patch upstream

I’ve sent a patch to the Linux kernel security team (security@kernel.org) because I wanted to err on the safe side: a memory corruption issue that could overwrite the memory of the processes’s states could have security implications. Unfortunately, this mailing list is private so I cannot link to the original patch I sent. Michael Ellerman, the PowerPC maintainer, followed up and told me he will contact me in private to figure this issue out. I have actually sent him two patches fixing the issue: the original one that I sent to the security mailing list and another version (quite different from the first one) which addressed some suggestions received in reply to my original submission. And the latter patch was actually based on existing kernel code, which emulated PowerPC32 operations on PowerPC64 (yeah, they got the FPR indexing right). Neither of those were accepted by Michael Ellerman, and instead he implemented his own version of the fix. I told him that I would really appreciate if he could accept a patch from me, so that I could receive credit for fixing this issue and become a kernel contributor. I was also open to working with him, addressing his feedback and sending subsequent versions of patches. He said (paraphrasing):

Sorry, I like my version better. If you want to be a Linux kernel contributor, here’s an issue you could fix.

I found this really perplexing and insulting. Instead of getting recognized for fixing the issue, he wanted to give me more work to do. My company and I should have received proper credit for solving this issue, especially considering how much effort we put into it.

I felt it was really unfair to only get a “Reported-by” tag. Here’s the purpose of the tag:

The Reported-by tag gives credit to people who find bugs and report them and it hopefully inspires them to help us again in the future.

Well, I certainly didn’t feel inspired to get involved with the kernel community again. On the contrary, I felt belittled and angry that my work wasn’t properly recognized.

Conclusion

I spent a lot of time and effort doing root cause analysis, fixing the bug, testing and validating the fix, getting feedback from other engineers at my company, adapting the fix to the latest kernel version, and sending two different patches to Michael Ellerman, the PowerPC maintainer. Instead of accepting my patch or guiding me towards a better solution, he went ahead and implemented his own fix, giving me credit only for reporting the issue (which was already reported six years prior to this).

My first contribution to the kernel was a really frustrating and discouraging experience, dealing with people who do not think it’s important to get proper recognition for your work.

Update

A user on Hacker News pointed out to this email in which Michael Ellerman says:

Thanks for your patch, but I wanted to fix it differently. Can you try the patch below and make sure it fixes the bug for you?

which highlights that the maintainer didn’t review my patch, but instead he went with his own implementation which he asked me to test.

I also found the original patch I sent to the security mailing list and forwarded the email thread to linuxppc-dev.

Hi Ariel,

I’m sorry about the way I handled your patch. I should have spent more time working with you to develop your patch.

I agree that the Reported-by tag doesn’t properly reflect the contribution you made, I should have realised that at the time.

cheers

(Apologies for the brief reply, I’m on vacation and replying from my phone)